I first met Bill Deller after coming back from overseas in 1986. People kept telling me I had to meet Bill Deller. After leaving the Socialist Labor League, Bill had got as far away from Left-wing politics as possible and was working in the Education Department. But his colleagues desperately needed a decent union and had finally prevailed on Bill to run for Departmental Section President for the VPSA. This had thrown Bill into a crisis because he did not believe he had the right to hold a union post as an individual, that is, not subject to Party discipline.

So he came round to see me and presented me with his quandary. I congratulated him on his decision to run for the position and told him that I had total confidence in his ability to withstand the pressures of bureaucracy, and in any case, it was his union members that he was subject to, not any party. Lynn Beaton and Bill and I formed a small group, which for a short time re-wrote the book on how to be a communist, and over the 28 years since then, there is hardly a Left project in Victoria in which Bill has not been involved.

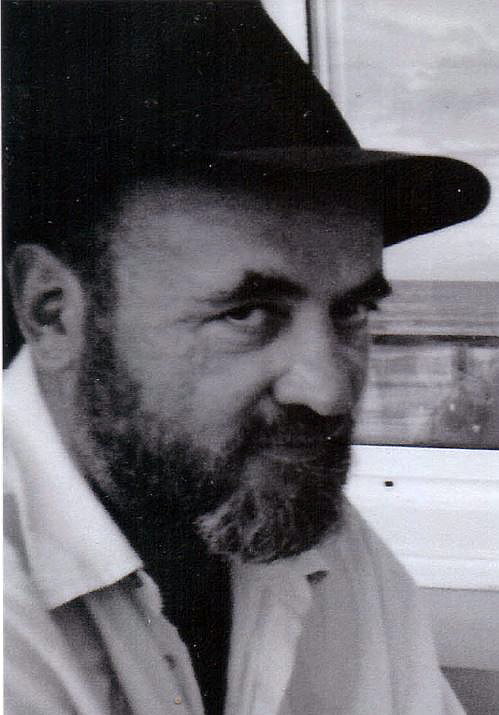

Bill had charisma. And he could walk stone cold into a meeting and pick up the sense of the meeting very quickly. These two gifts allowed Bill to draw people together and then raise people’s expectations and give them confidence in their new-found direction. Bill always used his talent to support the underdog. No matter how downtrodden and marginalised you were, Bill was confident that you could do it, whatever it was; and he would have your back, and stick by you when things got tough. Bill was the loyalest friend you ever had. Whenever you needed rescuing, ... Bill was your man.

What is possibly known only to those who were close to Bill, however, is this. To offer leadership in the way he did you have to exude confidence in the rightness of what you are proposing, and for that you need to totally believe in it yourself. As a result many leaders are arrogant, egotistical people. But Bill was not. In fact he often doubted himself, and he really needed the support of those around him to talk things through. He was very conscious of the impact of what he did and was always troubled about whether or not he was on the right track. For this he needed comrades whom he could trust and with whom he could discuss as equals. It was not about the party line, but about open and comradely discussion.

But whatever it was, Bill was sure that it could be done. He also knew that conviction grew out of conviction, and in fact he had great instincts. Not only could he gauge the sense of a meeting, he also had long-term vision, and the ability to motivate himself and others with long-term goals.

Bill was a boundary-crosser. He was a Trotskyist who made political alliances with honest right-wingers in the VPSA, bridged between the Left groups and the Churches in the Peace Movement. He was the fiercest defender of every employee or student in trouble at Latrobe, but never shied of advising the Vice-Chancellor. He was a white fella (so far as we know) who was trusted in the Koori community. He was a baby-boomer who mixed with Gen-Ys. He spent countless hours travelling between Melbourne and the country towns usually excluded from left politics because no-one else had ever been willing to put in the hours needed to cross this particular boundary. His boundary crossing also got him into trouble quite a lot. He couldn’t help it. But this willingness to cross any boundary is a liberating force. He was a postmodern kind of communist, always dissolving boundaries in a way quite uncharacteristic of Left politics. He crossed boundaries but he never compromised on principle.

As is the tradition for eulogies, I have focussed on Bill’s personal characteristics and virtues. Bill hasn’t left an institutional legacy, there are no buildings named after him, not even a book, only his example.

Bill’s party was in fact the working class itself. This is what we had first worked out in Communist Intervention, that small group – not to solve problems amongst ourselves and then deliver a solution to the working class, but to tackle problems together with the people who were experiencing them.

What he has left us is an exemplar of how to be a communist in these times. In that sense, this is not just about Bill’s personality and abilities. Much of what Bill practised can be learnt and can be emulated. We should all be impatient with petty rivalries, dogmas and boundaries. We should all cultivate a long-term vision. We should all develop that same confidence in the ordinary person. We should all have each others’ back.

It will take us a little time to process what we have learnt from Bill, but I think it a matter of great importance that we do.